When your stomach feels bloated after a small meal, you’re gassy for no reason, and diarrhea or constipation won’t quit - it’s easy to blame it on stress or bad food. But for many people, the real culprit is something deeper: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, or SIBO. It’s not just indigestion. It’s bacteria where they shouldn’t be - too many, in the wrong place. And it’s more common than most doctors admit.

What Exactly Is SIBO?

Your small intestine is meant to be mostly clean. It’s where nutrients get absorbed, not where bacteria hang out. But when bacteria from your colon creep up and multiply - more than 100,000 per milliliter - that’s SIBO. These bugs ferment food before it’s digested, producing gases like hydrogen and methane. That’s what causes the bloating, the pain, the burping, and the bowel chaos. It doesn’t happen overnight. SIBO builds when your body’s natural defenses break down. Think slow digestion from diabetes or Parkinson’s, past bowel surgery, long-term use of acid-reducing drugs like omeprazole, or even just having IBS. In fact, up to 85% of people diagnosed with IBS might actually have SIBO. The line between the two is blurry, and that’s why so many people get stuck in a cycle of treatments that don’t work.How Do You Test for It? The Breath Test

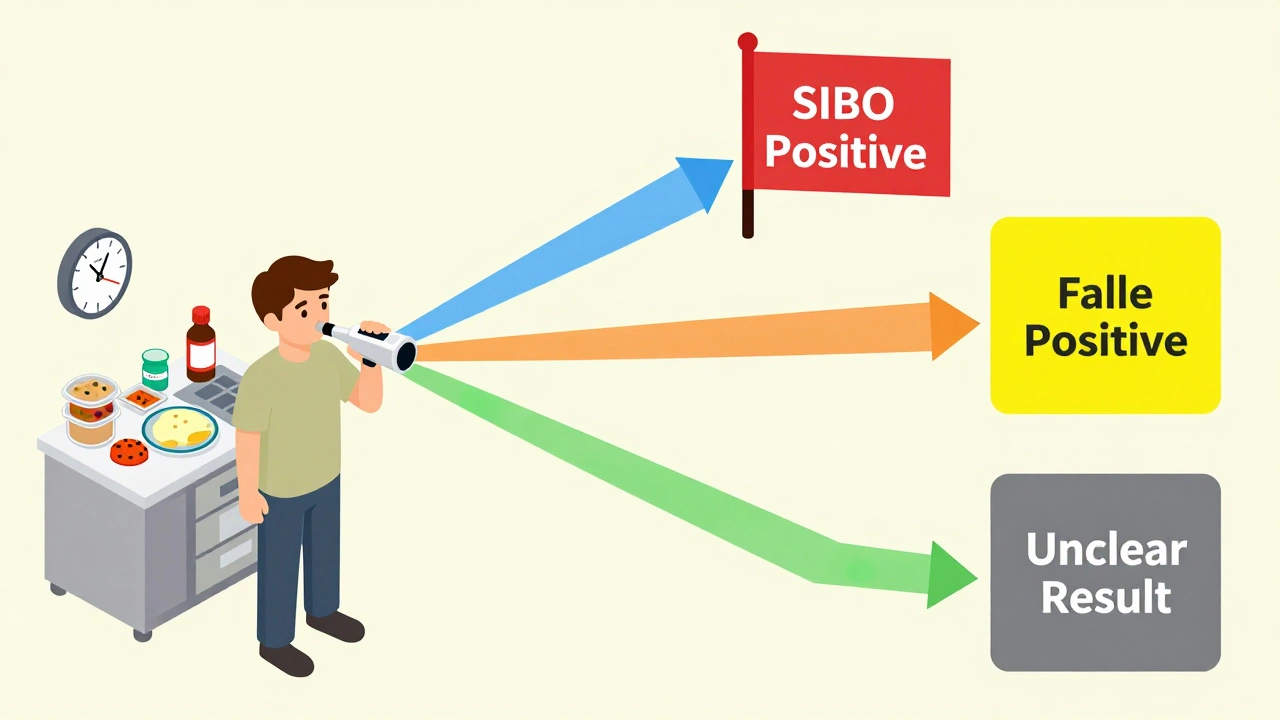

There’s no blood test. No scan. The go-to method? A breath test. It sounds simple: you drink a sugary solution, then blow into a bag every 15 to 20 minutes for two hours. But the details matter - a lot. There are two main types: glucose and lactulose. Glucose gets absorbed quickly in the first part of the small intestine. If you’re producing hydrogen or methane soon after drinking it, that’s a red flag - bacteria are there too early. Lactulose travels further, so it can catch bacteria deeper down. But it’s trickier to read. One study found glucose tests are more specific (83% accurate when they say you have it), but miss nearly half the cases. Lactulose catches more, but gives false positives in about 30% of people with fast digestion. The rules before the test are strict. You can’t eat for 12 hours. No antibiotics for four weeks. No laxatives or prokinetics for seven days. Even chewing gum or smoking can mess it up. And if you’re constipated? You might need extra prep. Skip these steps, and your test could be wrong - and you’ll end up on the wrong treatment.

Why Breath Tests Are Controversial

Here’s the problem: breath tests aren’t perfect. They don’t tell you which bacteria are overgrowing. They can’t tell if it’s hydrogen-dominant, methane-dominant, or both. And methane? That’s a whole different beast. Methane slows your gut down, causes constipation, and often needs a different mix of antibiotics than hydrogen. Some experts, like Dr. Hisham Hussan at UC Davis Health, say breath tests are only about 60% accurate. He’s one of the few in Northern California offering direct small intestine fluid sampling - a more invasive but precise method. A sample taken during an endoscopy can tell you exactly what bacteria are there and which antibiotics they respond to. But it’s expensive, not widely available, and requires an experienced endoscopist. Meanwhile, breath tests are everywhere. They cost $150 to $300. Endoscopic culture? $1,500 to $2,500. Most clinics don’t have the equipment or training to do it right. And labs interpret results differently - some call a 10 ppm rise positive, others demand 20 ppm. That’s why two people with the same symptoms can get opposite results.What Happens After a Positive Test?

If your test comes back positive, the usual first step is antibiotics. Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is the most common - 1,200 mg a day for 10 to 14 days. It doesn’t get absorbed into your bloodstream, so it stays in your gut. About 50% of people feel better. But here’s the catch: more than 40% come back within nine months. If methane is high, rifaximin alone often fails. You need to add neomycin - a second antibiotic. That combo works better for constipation-predominant cases. Some doctors try herbal antimicrobials like oregano oil, berberine, or allicin. Studies show they can be as effective as antibiotics for some, with fewer side effects. But they’re not regulated like drugs, so quality varies. Treatment isn’t just about killing bacteria. You need to fix why they came back. That means addressing slow motility, healing the gut lining, and sometimes reducing acid blockers if they’re part of the problem. Prokinetics like low-dose naltrexone or prucalopride help your gut move again. Diet helps too - low FODMAP or SIBO-specific diets can reduce symptoms while you’re treating it.

Courtney Blake

December 10, 2025 AT 13:56Also, stop eating garlic. Just stop.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 11, 2025 AT 12:40Michaux Hyatt

December 13, 2025 AT 10:03And yes, oregano oil works for some. Just don't buy the $80 bottle on Amazon. Look for standardized berberine.

Raj Rsvpraj

December 14, 2025 AT 21:30Stephanie Maillet

December 16, 2025 AT 14:15Also, I've seen people heal with just fasting + walking. No drugs.

Ariel Nichole

December 17, 2025 AT 07:24Kaitlynn nail

December 18, 2025 AT 12:01Rebecca Dong

December 20, 2025 AT 05:21Nikki Smellie

December 20, 2025 AT 16:32Neelam Kumari

December 20, 2025 AT 21:31Queenie Chan

December 22, 2025 AT 06:49Paul Dixon

December 22, 2025 AT 15:57john damon

December 23, 2025 AT 02:07Monica Evan

December 24, 2025 AT 08:37Taylor Dressler

December 25, 2025 AT 10:16