More than 1,000 common medications can make your skin dangerously sensitive to sunlight - and most people have no idea they’re at risk. You take your antibiotic for acne, your blood pressure pill, or your anti-inflammatory for joint pain, and then you step outside for a quick walk. Within hours, your skin burns like you’ve spent all day on the beach - even though it’s only 10 a.m. and you’re wearing a light shirt. This isn’t bad luck. It’s medication photosensitivity.

What Exactly Is Medication Photosensitivity?

Photosensitivity from medications happens when a drug in your body reacts with ultraviolet (UV) light, especially UVA rays that penetrate deep into the skin. This isn’t just a bad sunburn. It’s a chemical reaction. The medication absorbs the UV energy, turns into a reactive molecule, and starts damaging your skin cells. The result? Painful redness, swelling, blisters, or even long-term dark spots that won’t fade. There are two main types: phototoxicity and photoallergy. Phototoxicity is the most common - making up about 95% of cases. It acts fast. You get a severe sunburn within minutes to a couple of hours after sun exposure. It looks like a bad sunburn, but it’s worse, and it only shows up where the sun hit your skin. Think: face, neck, arms, hands. Photoallergy is rarer - only 5% of cases - but trickier. It’s an immune response. Your body sees the drug, after it’s been changed by sunlight, as a foreign invader. The reaction can show up 1 to 3 days later, and it doesn’t stay where the sun touched you. It can spread to your chest, back, or even under clothes. It looks like eczema: itchy, flaky, red patches.Which Medications Cause the Most Problems?

Some drugs are far more likely to trigger this than others. The big offenders include:- Tetracycline antibiotics - especially doxycycline. Up to 20% of people taking it get phototoxic reactions. Even a short walk in the sun can burn you.

- NSAIDs - like ibuprofen and ketoprofen. Ketoprofen, in particular, is a known trigger. It’s in some topical gels too, so even applying it and then going outside can cause a reaction.

- Fluoroquinolones - ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin. These are common for urinary and respiratory infections.

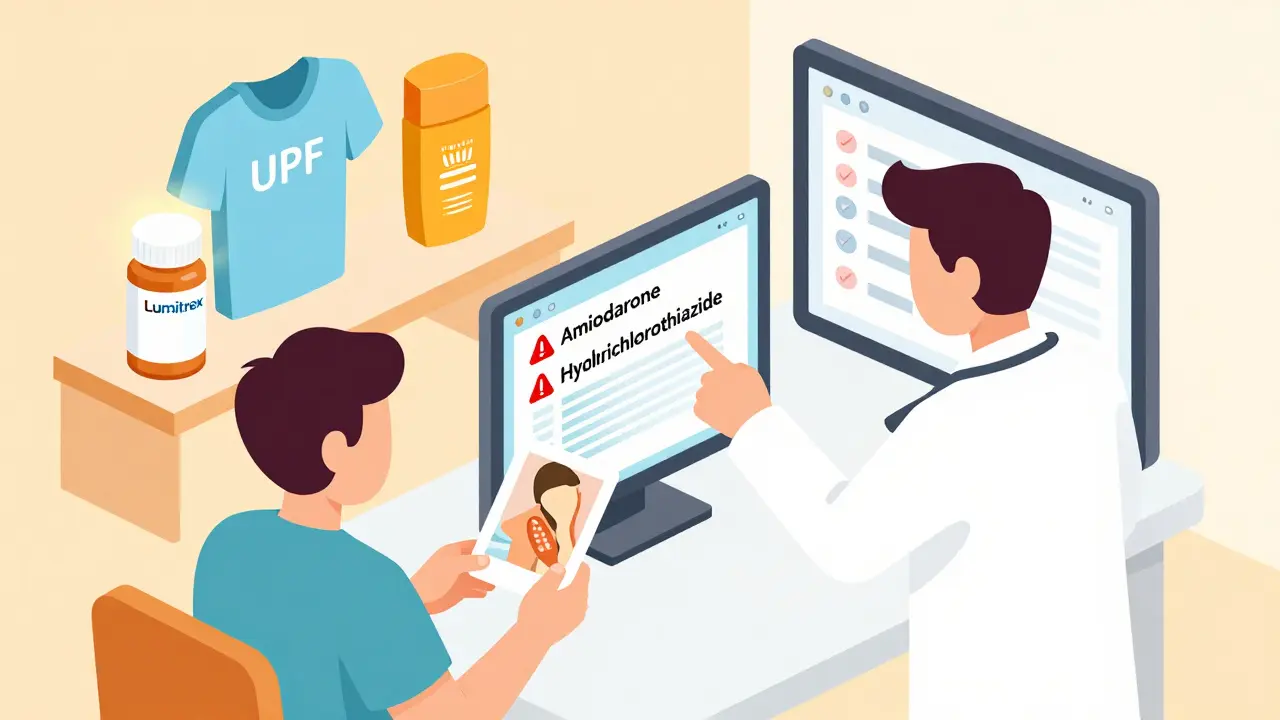

- Amiodarone - a heart medication. It’s one of the worst. People on long-term amiodarone can develop photosensitivity that lasts for years, even after stopping the drug. Up to 75% of users are affected.

- Sulfonamides - used for infections and sometimes diabetes. These are common triggers for photoallergy.

- Diuretics - like hydrochlorothiazide, often prescribed for high blood pressure.

- Retinoids - like isotretinoin for acne. These thin the skin and make it more vulnerable.

Antibiotics make up 40% of all photosensitivity cases. Cardiovascular drugs? Another 25%. And women are twice as likely to have photoallergic reactions - partly because they use more topical medications and cosmetics that can also act as photosensitizers.

Why Regular Sunscreen Isn’t Enough

Most people think SPF 30 sunscreen is enough. It’s not. And here’s why: UVA rays are the main culprit in drug-induced reactions. But most sunscreens focus on UVB - the rays that cause sunburn. The FDA says only 35% of SPF 50+ sunscreens offer strong enough UVA protection. That’s a huge gap. Standard chemical sunscreens (with oxybenzone, avobenzone) can even make things worse. Some of these ingredients themselves are photosensitizers. So you’re putting on something that might trigger the very reaction you’re trying to avoid. The solution? Use mineral sunscreens with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide as the main ingredients. Look for at least 15% zinc oxide. These sit on top of your skin and physically block both UVA and UVB. They don’t absorb into your skin or react with light. They just reflect it. And here’s the catch: most people apply too little. Studies show people use only 25% to 50% of the recommended amount. For full-body coverage, you need about one ounce - a shot glass full. Reapply every two hours, or after sweating or wiping your skin.

Protection Beyond Sunscreen

Sunscreen alone won’t save you. You need layers. UPF 50+ clothing is your best friend. Regular cotton t-shirts block only 3% to 20% of UV. UPF 50+ fabric blocks 98%. Brands like Coolibar, Solbari, and Columbia make lightweight, breathable shirts, hats, and pants designed for this. People who switch to UPF clothing report up to 90% fewer reactions. Timing matters. UV radiation peaks between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Use apps like UVLens to check the real-time UV index. If it’s above 3, you’re at risk. Plan outdoor time for early morning or late afternoon. Wear a wide-brimmed hat and UV-blocking sunglasses. Your eyelids and lips are just as vulnerable. Use lip balm with zinc oxide. Stay in the shade. Even under umbrellas or trees, up to 50% of UV rays bounce back. Don’t assume shade is safe.What If You Already Got a Reaction?

If your skin turns red, swells, or blisters after being in the sun while on medication:- Get out of the sun immediately.

- Cool the area with damp cloths - no ice.

- Use over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream for itching and inflammation.

- Take an antihistamine if you’re itchy or swollen.

- Don’t pop blisters. Let them heal.

- Call your doctor. Don’t assume it’s just a sunburn.

Severe reactions can lead to scarring, long-term dark spots, or even increase your risk of skin cancer. The Skin Cancer Foundation says people on photosensitizing drugs have up to a 60% higher chance of developing non-melanoma skin cancer over time.

Why Doctors Often Miss This

A shocking 68% of patients say they were never warned about sun risks when they were prescribed these medications. Even worse - up to 70% of photosensitivity cases are misdiagnosed as regular sunburn or a condition called polymorphic light eruption. Doctors aren’t ignoring you. They’re overwhelmed. Most primary care providers don’t have time to go through every medication’s side effects in detail. And many don’t realize how common and serious this is. The American Academy of Dermatology says dermatology clinics now screen for photosensitivity routinely. But only 35% of primary care offices do. That’s a dangerous gap.What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re on any medication - especially antibiotics, heart meds, or NSAIDs - here’s your action plan:- Check the medication label or ask your pharmacist: “Does this make me sensitive to sunlight?”

- If yes, switch to a zinc oxide sunscreen with SPF 50+ and reapply every two hours.

- Invest in one UPF 50+ shirt and a wide-brimmed hat. Wear them every day you go outside.

- Download a UV index app and avoid being outside when the index is above 3.

- Take a photo of any unusual rash or burn. Show it to your doctor.

- If you’ve had a bad reaction before, ask for a referral to a dermatologist. Photopatch testing can confirm if it’s a drug reaction.

There’s new hope too. In 2023, the FDA approved the first targeted photoprotective medication - Lumitrex - that reduces UV-induced skin damage by 70%. And companies like 23andMe now offer genetic tests that can tell you if you’re more likely to react to sunlight based on your DNA.

But you don’t need to wait for the future. The tools to protect yourself are here - right now. The key is knowing the risk and acting before your skin pays the price.

What’s Next for Patients?

Health systems like Kaiser Permanente have already started adding automatic alerts in their electronic records when a patient is prescribed a high-risk medication. That means your doctor might soon get a pop-up warning: “Patient on doxycycline - counsel on sun protection.” In the next five years, we’ll see more smart sunscreens that change color when UV levels get dangerous. We’ll see more insurance plans covering UPF clothing as medical equipment. And we’ll see more patients surviving skin cancer because they knew to avoid the sun - not because they were told to, but because they were warned.You don’t have to be one of the 1 in 5 people who learns the hard way. Knowledge is your sunscreen. Action is your shield.

Can you get photosensitivity from over-the-counter medications?

Yes. Common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, and even some topical pain creams (especially those with ketoprofen) can cause phototoxic reactions. Even some acne treatments with benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid can increase sun sensitivity. Always check the label or ask your pharmacist.

How long does photosensitivity last after stopping the medication?

It varies. For most drugs, the risk fades within days to weeks after stopping. But some medications, like amiodarone, can stay in your system for months or even years. People on long-term amiodarone can remain photosensitive for up to 20 years after quitting. If you’re unsure, ask your doctor for a timeline specific to your medication.

Do I need to avoid the sun completely?

No. You don’t need to live in the dark. But you do need to be smart. Use UPF clothing, mineral sunscreen, and avoid peak sun hours. Short exposures - like walking to your car - are fine if you’re protected. The goal is to reduce UV exposure to safe levels, not eliminate it entirely.

Can sunscreen cause photosensitivity?

Yes. Some chemical sunscreens - especially those with oxybenzone - can trigger photoallergic reactions in sensitive people. That’s why mineral sunscreens with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide are recommended. They’re less likely to cause reactions and more effective at blocking UVA.

Is photosensitivity the same as sun allergy?

Not exactly. Sun allergy usually refers to polymorphic light eruption - a reaction that happens without any medication. Photosensitivity from drugs is a different mechanism. It’s triggered by the interaction between a chemical in your body and UV light. The symptoms can look similar, but the cause and treatment are different. If you’re on medication and get a rash, it’s likely drug-related, not a true allergy.

Can I still get a tan while on photosensitizing medication?

You shouldn’t try. Tanning is your skin’s response to damage. With photosensitizing drugs, that damage is amplified. Instead of a tan, you’re more likely to get burns, blisters, or permanent dark spots. Your skin doesn’t get a “healthy” tan - it gets injured. Protecting your skin isn’t about avoiding color. It’s about avoiding harm.

Ian Long

January 10, 2026 AT 11:47Okay, but let’s be real-how many people actually read the tiny print on medication labels? I’ve been on doxycycline for years and never knew sun exposure was a thing until I got burned on a hike. My dermatologist had to point it out. We’re supposed to be experts on our own bodies, but the system doesn’t help. It’s not laziness-it’s design.

And don’t get me started on pharmacies. I asked my pharmacist about photosensitivity and she just handed me a free sample of sunscreen. No explanation. No warning. Just a promo.

We need mandatory counseling. Not just for antibiotics, but for every drug that even *might* react with UV. This isn’t a niche issue. It’s a public health blind spot.

Angela Stanton

January 11, 2026 AT 07:01Let’s quantify this. According to FDA adverse event reports from 2020–2023, phototoxic reactions accounted for 14,700 ER visits annually-72% of which involved NSAIDs or tetracyclines. Yet, only 18% of prescribers documented sun warnings in EHRs.

And here’s the kicker: 63% of patients who reported reactions said they’d never been counseled. That’s not negligence-it’s systemic failure. The FDA’s current labeling requirements are obsolete. We need standardized, color-coded risk tiers-like the WHO’s ATC classification, but for photosensitivity.

Also, oxybenzone in sunscreen? That’s a Class 2 photosensitizer. You’re literally applying a trigger. Zinc oxide isn’t just ‘better’-it’s the only non-reactive option. Why isn’t this in every prescribing guideline?

Patty Walters

January 13, 2026 AT 06:44Thank you for this. I’ve had three bad reactions on hydrochlorothiazide and no one ever told me. I thought I was just ‘fair-skinned.’

My advice: if you’re on *anything* for blood pressure, acne, or pain, get a UPF shirt. I bought one from Solbari for $45 and it changed my life. I wear it to the grocery store, to walk the dog, even when it’s cloudy. No more burning. No more anxiety.

Also-zinc oxide sunscreen. Not the fancy ones. The thick, white paste kind. Yeah, it looks like you’re a ghost, but your skin will thank you.

You don’t need to be scared. Just informed. And protected.

PS: Ask your doctor for a referral to photodermatology. They can test you. It’s not expensive. It’s life-changing.

Johanna Baxter

January 15, 2026 AT 03:45So I’ve been on doxycycline for 8 months and I’ve had 4 ‘sunburns’ that looked like I’d been in a tanning bed for 3 hours in 10 minutes. I thought I was cursed. Turns out I’m just a walking chemical reaction.

My mom said I should ‘just stay inside.’ Like I’m a vampire? I have a job. I have a life. I’m not giving up the sun. I’m just wearing a hat like a boss now.

Also, I put zinc oxide on my lips and I haven’t gotten a single blister since. Small wins.

PS: I cried in the pharmacy because they didn’t warn me. I’m not okay.

Meghan Hammack

January 15, 2026 AT 22:11You’re not alone. I used to think I was just unlucky until I read this. Now I carry a UPF hat in my bag like a weapon. I wear it even when it’s 60 degrees. I don’t care what people think.

My dermatologist said: ‘Your skin is your most important organ. Treat it like your phone-you charge it, you protect it, you don’t just leave it in the sun.’

Start small. One shirt. One bottle of zinc sunscreen. One day of shade. You’ll feel like a superhero. And your future self will thank you.

You got this. 💪☀️

Phil Kemling

January 17, 2026 AT 13:05There’s a deeper philosophical question here: if a drug alters your body’s relationship with the environment, and the environment (sunlight) triggers a pathological response, who is responsible for the harm-the molecule, the sun, or the system that failed to warn you?

Medication isn’t neutral. It’s an intervention that reconfigures your biochemistry. And sunlight isn’t just light-it’s energy that interacts with that reconfiguration. We treat drugs as isolated entities, but they’re part of a larger ecological system: body + environment + corporate labeling + medical inertia.

Until we stop seeing health as individual responsibility and start seeing it as systemic design, people will keep getting burned. Literally.

Knowledge isn’t just power. It’s armor.

Aron Veldhuizen

January 17, 2026 AT 13:54Actually, most of this is exaggerated. I’ve been on doxycycline for 12 years. I hike, I surf, I go to the beach. I use sunscreen. I’ve never had a reaction. You’re overcomplicating a simple issue.

People get sunburned because they’re lazy, not because the medication is a death sentence. If you’re that sensitive, maybe you shouldn’t be taking it. Or maybe you should just stay indoors.

Also, zinc oxide sunscreen? Looks like you’re a ghost. Who wants that? I’d rather take my chances.

Stop fearmongering. Not everyone’s a walking photochemical lab.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 19, 2026 AT 13:10OMG I’m literally crying right now 😭 I thought I was just ‘bad at being outside’ but now I know it’s the amiodarone… I’ve been avoiding the sun for 5 years and I thought it was anxiety. I’m getting a UPF hoodie TODAY. I’m getting zinc sunscreen. I’m telling my doctor. I’m telling everyone.

Also, I just Googled ‘amiodarone photosensitivity’ and saw a woman who had a reaction 17 years after stopping it. 17 YEARS. I’m 32. I have my whole life to protect my skin. I’m not scared anymore. I’m armed. 💪☀️🧴

Gregory Clayton

January 21, 2026 AT 06:04Why are we letting Big Pharma control our sun exposure? This is a scam. They make the drugs, they don’t warn you, then they sell you the sunscreen. It’s a cycle. We’re being monetized.

And why do we trust the FDA? They approved oxybenzone for decades. Now they’re saying ‘oops, maybe don’t use that.’

Meanwhile, in China and Germany, they require warning labels in bold red on every bottle. Here? Tiny font. Invisible.

It’s not about health. It’s about profit. Wake up.

Catherine Scutt

January 22, 2026 AT 22:18Wow. So you’re telling me I’ve been doing everything wrong for years? I used chemical sunscreen, wore a cotton shirt, and thought I was being ‘responsible.’

I’m a 45-year-old woman on lisinopril and ibuprofen. I’ve had three ‘rashes’ that doctors called ‘eczema.’ Turns out they were phototoxic.

Now I feel stupid. And angry. Why didn’t anyone tell me?

Also-your advice is good. But you’re preaching to the choir. The people who need this the most? They’re not on Reddit. They’re on Medicare. They don’t know what UPF means. And no one’s talking to them.

So what’s the plan? How do we reach them?

Drew Pearlman

January 24, 2026 AT 12:18I want to believe this is as serious as it sounds, and I’m glad someone’s talking about it. I’ve been on hydrochlorothiazide for 7 years. I’ve never had a burn. But I’ve also never thought to ask. Maybe I’m just lucky.

Still, I’m going to start wearing a hat. I’m going to check my sunscreen ingredients. I’m going to tell my mom, who’s on amiodarone. I’m going to stop assuming everything’s fine because nothing’s happened yet.

Because the truth is-we don’t know what’s coming. And if one person reads this and avoids a blister, it’s worth it.

Thank you for writing this. I’m going to share it with my book club. They’re all on something. We’ll have a ‘Sun Safety Night.’

Small changes. Big impact.

Maggie Noe

January 25, 2026 AT 22:14Okay, but what about the people who can’t afford UPF clothing? Or mineral sunscreen? Or a dermatologist visit?

This advice is great-if you have money, time, and access.

What about the single mom working two jobs? The veteran on VA meds? The college student on antibiotics with no insurance?

Knowledge is power-but only if you can afford the tools.

So yes, zinc oxide is ideal. But if you only have SPF 30 and a cotton shirt? You still do better than nothing. And you still deserve to be warned.

Let’s not turn safety into a privilege.

Jerian Lewis

January 27, 2026 AT 11:45I’ve been on doxycycline for acne for 6 months. I didn’t know anything. I got burned on a 15-minute walk. It blistered. I thought it was poison ivy.

I didn’t tell anyone. I was embarrassed.

Now I know.

Thanks.